MILAN,

The Renaissance in Milan

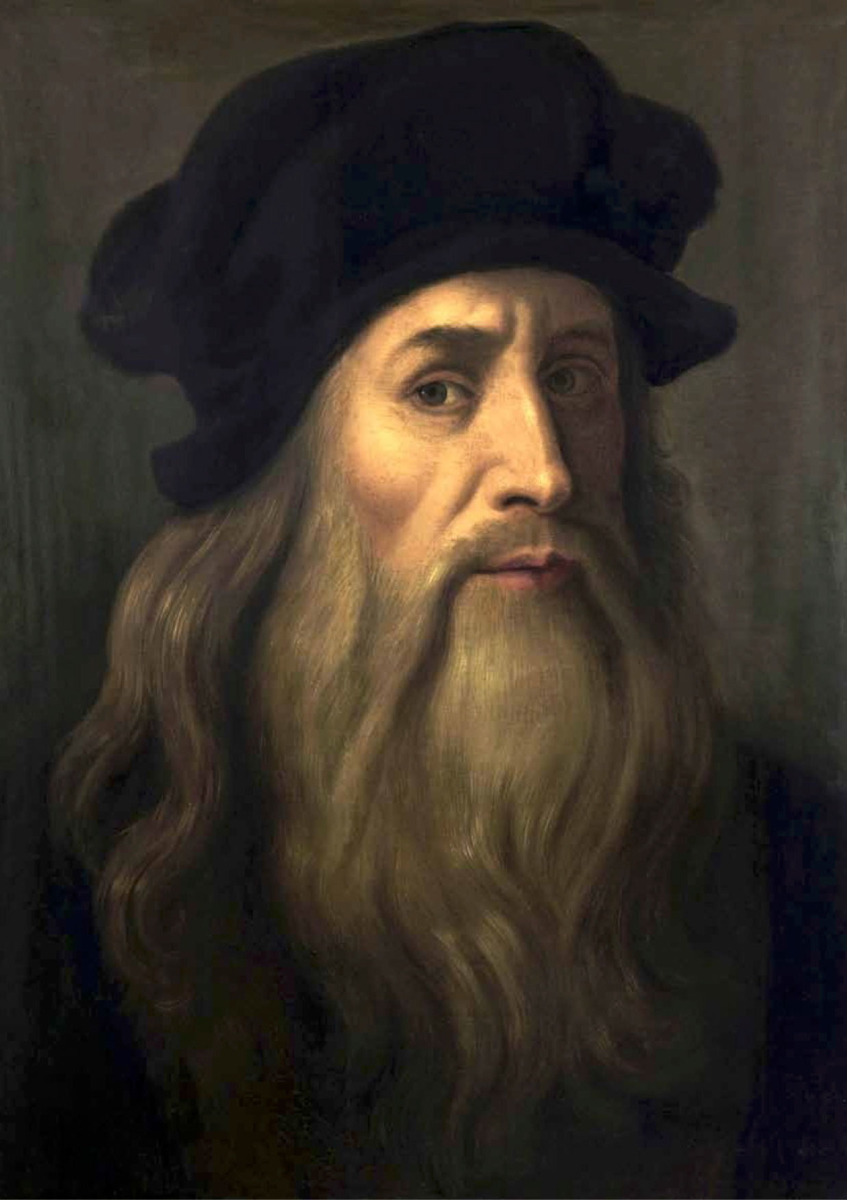

In 1482 Leonardo da Vinci, now thirty years old, left Florence where he had produced his first masterpieces in the humanist circle of Lorenzo il Magnifico. In search of new horizons where to expand his creative genius, and powerful patrons to support it, he turned towards Lombardy’s capital city.

He sent a letter to Ludovico il Moro, Duke of Milan, describing his own talents in ten concise points. Oddly enough the first nine of them did not mention art and architecture but listed an inventory of various arms and war machines. Only the last one mentioned his talents as a civil engineer, and at the end as an artist. His proposal was favorably accepted by the Duke, and Leonardo moved to Milan where he lived for the next eighteen years creating further masterpieces.

Thus The Virgin of the Rocks (1483–1486), now in the Louvre Museum in Paris, a later version in the National Gallery in London, settled his fame and secured his appointment at the Ducal Court. Soon after Leonardo moved to the Palazzo Visconti, the Old Court near the Duomo, and Ludovico il Moro entrusted him with several prestigious commissions: the portrait of his mistress, Cecilia Gallerani (the Lady with an Ermine c. 1489), the decoration in trompe-l’oeil of the Sala delle Asse in Palazzo Sforza, 1498, as well as the famous Last Supper for the refectory of the Dominican convent of Santa Maria delle Grazie (1495-1496). Leonardo designed also the stage sets for the celebration of the wedding between the Houses of Este and Aragon. He was involved in town planning, religious and civil architecture and various works of civil, hydraulic and agricultural engineering. His influence on Milan’s artistic scene endured in the sixteenth century fostering the school of the leonardeschi : Boltraffio, Andrea Solario, Cesare da Sesto and Bernardino Luini among others.

In the fifteenth century the Visconti family had given back to Milan the prestige it had enjoyed a thousand years before as the last capital of the Roman Empire. They had carefully planned an agricultural and industrial policy, thus in the production and weaving of silk, also woven with gold thread, a technique for which the city became known as the first in the world. In architecture the Visconti dynasty favored the International Gothic style fostered on by their alliance through marriage with the French Valois royal family.

The Renaissance style came to the city thanks to Francesco Sforza who brought to his court the Florentine architect and sculptor Filarete. But it was his son Ludovico Sforza, known as Il Moro, who in calling major Renaissance artists to his service, among them Bramante and Leonardo da Vinci, ensured the fame and influence of Milan as an important European artistic centre.

The production of luxury wares

It was not only for its outstanding architecture, sculptures and paintings that Milan became one of the main European centre for the production of luxury wares, but rather for the wondrous works of art the Milanese craftsmen created for an international elite: emperors, kings and princes, aristocrats, and other wealthy art lovers.

Made in Milan had already become a brand mark of excellence for arms and armours. Similarly many other applied arts achieved this high standard, first of all the production of exquisite silk fabrics such as damask and lampas, and the art of the goldsmith and enameller.

Milan assumed also a leadership in fashion, in the dowry of European aristocratic families some items of clothing are mentioned as Lombardi or Milanesi.

As early as the fifteenth century, under the Visconti rule, Milan goldsmiths and armourers were renowned for their excellence, producing wares of the highest quality. Milanese armours were particularly prized for their magnificence as the most precious and costly item of masculine fashion. The sumptuous creations of famous armourers such as the family firms of Missaglia or Negroli, Giovanni Battista Panzieri called Zarabaglia, Lucio Marliani called Piccinino, were coveted by all ruling and ducal courts. It has to be noted that, quite often, these metalworkers practiced the ready-made as well as the bespoke production.

Among other internationally renowned luxury wares from Milan, the production of illuminated manuscripts, of finely worked furniture and leather goods of the highest quality were highly prized. This applied to all kinds of exquisite accessories, and everything else which then as now were the objects of desire of the true luxury lovers.

During the sixteenth century Milan’s luxury wares enjoyed such great fame for their particularly sophisticated artistic creativity, the use of precious materials and the high level of virtuosity that they became real status symbol. These luxurious objects grew to be the elite’s distinctive sign as a member of the aristocracy.

After the annexation of Lombardy to Charles V of Habsburg’s Spanish Austrian Empire, Milan became the heart of the monarchy, one of the most important cities of the Empire. From there the Habsburg’s troops in Flanders, Germany, Austria and Italy were paid their fee, which meant that Milan was the market place for a huge trade in gold and silver from the American colonies.

It allowed for the development of exclusive workshops where craftsmanship and inventiveness produced works of art on a large scale for an international market. All the streets in the centre of Milan, from the Duomo to Cordusio, record the names of the various districts where the goldsmiths, swords, armours and spurs makers and their traders had their business.

Wondrous wares were produced by the craftsmen in semi precious stones, pietre dure: vases, cups and ewers, goblets, salvers, caskets and other wares from the firms of Saracchi, Gasparo and Girolamo Miseroni, Jacopo Nizzola da Trezzo and Annibale Fontana, as well as the carved gems and cameos of Tortorino, Masnago and Girolamo Miseroni. The bronze creations of sculptors and medalists as Cristoforo Foppa named Caradosso and later Leone Leoni became real models admired and imitated throughout Europe.

The Lombard churches’ Treasuries still preserve in their ecclesiastical vestments some remnants of the marvelous silk and embroidery Milanese production. Some fragments of a secular nature are kept in the collection of the Castello Sforzesco, in the Museo Poldi Pezzoli and other international museums.

The production of precious works of art was aimed at the European ruling elite, and traded by the Kings and Princes’ agents.

Vases in rock crystal, Cabinets, carved pietre dure figures were meant for the most powerful protagonists of that time: among them Charles V and Phillip II of Spain, Rudolf II, the Duke Albert V of Bavaria, the Grand Duke Francesco de’ Medici, Guidobaldo II Della Rovere, Guglielmo, Vincenzo and Ferdinando Gonzaga, Carlo Emanuele I di Savoia and many other international personalities.

Many of these works of art were commissioned as diplomatic gifts. The great beauty and virtuosity of these objects were much appreciated and they kept by art lovers and connoisseurs in their Wunderkammern or Cabinets de Curiosités.

Thanks to the love and taste of those past patrons and collectors these works of art have survived. They can be admired in museums in Vienna, Madrid, Dresden, Munich, Paris and Florence and give rise to wonderment as to their fine craftsmanship and sublime conception.

This lavish production of outstanding luxurious wares is the reason why Milan can rightfully claim the status of a capital city in design and in the industry of luxury goods. Its reputation is rooted in its prestigious past first as the last capital of the Late Roman Empire and thereafter, from the sixteenth century onwards, as an artistic capital city.

This is why Manifattura Milanese intends to reclaim, first from its name and in its field of activity, the tradition of a city that is a symbol of creativity, elegance and fine exquisite craftsmanship.

BIBLIOGRAPHY:

Ferino-Pagden Sylvia, Le arti a Milano nel Cinquecento. in Made in Milano – Le botteghe del cinquecento,

Franco Maria Ricci 2016

Venturelli Paola, Leonardo da Vinci e le arti preziose. Milano tra XV e XVI secolo, Marsilio, Venezia 2002

Lopez Guido, La storia di Milano raccontata da Guido Lopez, in Enciclopedia di Milano dalle Origini ai giorni nostri, Franco Maria Ricci, 1998

AA.VV, Grandezza e Splendori della Lombardia Spagnola. Skira, Milano 2002

Isella Dante (a cura di) Giovanni Paolo Lomazzo, Rabisch, Einaudi, Torino 1993 (Nuova universale Einaudi 2012)

Beonio Brocchieri Vittorio, “Piazza universale di tutte le professioni del mondo”. Famiglie e mestieri nel ducato di Milano in età spagnola, Unicopli, Milano 2000

Kemp Martin “Equal Excellences”: Lomazzo And The Explanation of Individual Style in the Visual Arts,

in Renaissance Studies vol 1.1, March 1987

Morigia Paolo e Borsieri Girolamo. Ia Nobiltà di Milano descritta (...). Gio. Battista Bidelli, Milano 1619 Agosti Giovanni, Bambaia e il classicismo Lombardo, Einaudi, Torino 1990